Night falls at the Museum

Once upon a time, three men went forth together, brothers in arms. One was a Native American, one an African, one a pudgy and nearsighted white guy from New York who deployed his privilege to create a permanent legacy to conserve the wild and educate his country. Through his great anthropological and natural history museum, visitors would learn about the rich cultures of peoples they had once deemed savages, and the natural beauty and environmental importance of lands they knew only as swatches on a map, labeled by resource and conqueror. All three heroes had their eyes fixed on the future together--but in their rough-and-tumble world, they also kept their hands on their guns, anticipating a rough road ahead.

How rough a world, they could never have guessed. Generations of people from all over the world gazed up at them, drawn by the physical beauty and power of the two men on foot and their idealistic fellowship with the American conservationist and president. But then a mob came, and saw only oppression, saw only that the white guy got the horse. They threw paint, scrawled obscenities. They believed, not just that we were all too stupid to see that the fellowship walking out of the mists of history was a dream, dated perhaps but cloaked in dignity. They also howled that the dream itself was sour, poisoned and false, an insult and a lie to the oppressed. And the museum, conservator of history and its contexts, squirmed and "addressed" the monument with a special exhibition, but the mob was not satisfied. They howled all the louder.

And so the brothers in arms will be torn from their pedestal and hidden away, their gaze now fixed on a storeroom wall. Perhaps we could replace them with a statue of a mass of people gazing at Twitter and retweeting slogans. Because every monument is "of its day," and the pigeons, like the mob, will move on to the next perch.

'Because they are not human'

Hediya, age 9, enslaved by ISIS for 6 years. Photo: Adam Ferguson for the New York timesJan Kizilhan, a prominent Kurdish psychologist, works heroically with Yazidi refugees brutalized by ISIS. "I will never forget the story of one 8-year-old girl,” Kizilhan told the New York Times. “She was raped hundreds of times by dozens of men. She was so young and so small.”

Hediya, age 9, enslaved by ISIS for 6 years. Photo: Adam Ferguson for the New York timesJan Kizilhan, a prominent Kurdish psychologist, works heroically with Yazidi refugees brutalized by ISIS. "I will never forget the story of one 8-year-old girl,” Kizilhan told the New York Times. “She was raped hundreds of times by dozens of men. She was so young and so small.”

The children kept asking him: Why does ISIS do this to us? He didn’t have an answer, so he later went to a couple of prisons outside Kirkuk to interview captured fighters. "Over and over again, the fighters told him: We kill them because they are not human."

Because they are not human.

This. This is the answer to every "how could they" of our blood-drenched times. The "othering" into sub-humanity.

Awaiting death at Auschwitz. Image copyright Yad Vashem.How could they throw children into ovens in the camps?

Awaiting death at Auschwitz. Image copyright Yad Vashem.How could they throw children into ovens in the camps?

Well, they were only Jews, you see. And gypsies. And mental defectives. They were "life unworthy of life." THEY WERE NOT HUMAN.

The lynching of Laura Nelson in Okemah, Oklahoma, on May 25, 19How could they sell human beings like cattle, torture them and string them up for sport?

The lynching of Laura Nelson in Okemah, Oklahoma, on May 25, 19How could they sell human beings like cattle, torture them and string them up for sport?

They were blacks. THEY WERE NOT HUMAN.

How could the Japanese, a culture suffused with respect and delicacy, have made sex slaves of Korean women in wartime?

How could the Japanese, a culture suffused with respect and delicacy, have made sex slaves of Korean women in wartime?

They weren't our women. THEY WERE NOT HUMAN.

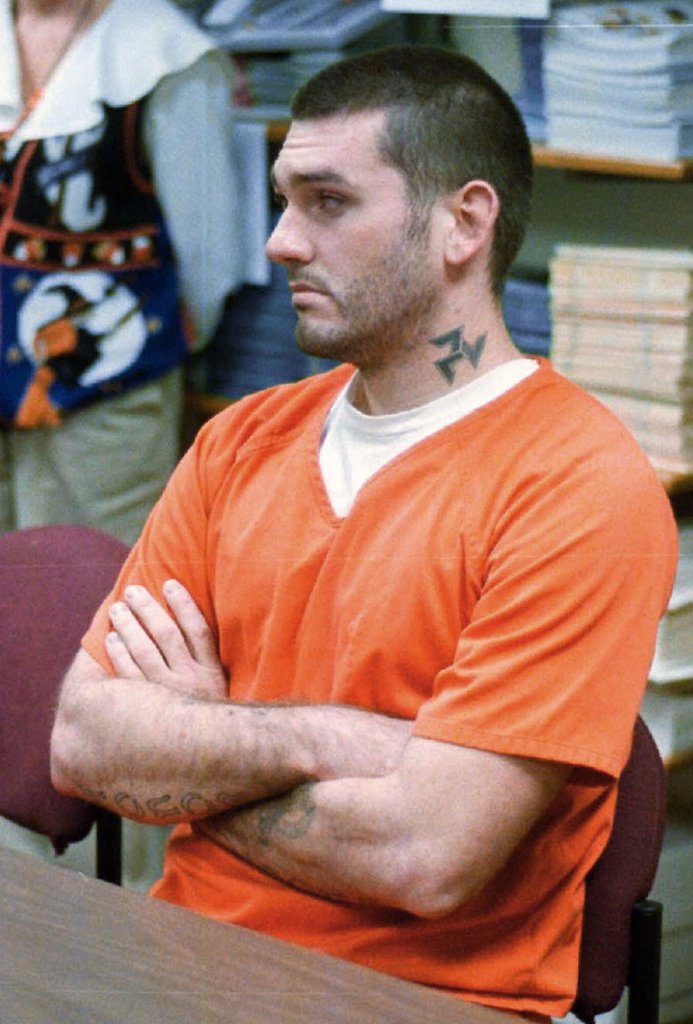

Daniel Lee, white supremacist murderer on Death Row. Photo: Dan Pierce, The Courier, via Associated Press

Daniel Lee, white supremacist murderer on Death Row. Photo: Dan Pierce, The Courier, via Associated Press

How do we justify executing prisoners?

Do you know what they've done, those guys on Death Row? They are monsters. Animals. THEY ARE NOT HUMAN.

Human child, 20 weeks gestation. Photo: Lennart Nillson.How does an abortionist dismember a late-term unborn child limb from limb, count up the pieces in a pan, and wash up for the next procedure?

Human child, 20 weeks gestation. Photo: Lennart Nillson.How does an abortionist dismember a late-term unborn child limb from limb, count up the pieces in a pan, and wash up for the next procedure?

It's legal. As long as they dwell within their mothers' bodies, THEY ARE NOT HUMAN.

How can we ignore the suffering of children in border detention, when such conditions would be unthinkable for our own children?

They're not like our children, not really. They are poor, and innumerable, and brown. They're human, but not...AS human.

And how will we start to justify euthanizing the terminally ill, the profoundly disabled, the comatose?

They are without hope, without consciousness, and surely that's what makes us most fully human. And they're terribly expensive to maintain, with scarce resources. It's almost like THEY ARE NOT HUMAN. Not anymore, right?

In honor of all those deemed "unworthy of life," perhaps we all need to ask ourselves from time to time:

Who do you manage to view as just a little less than human?

Biting the Dust: Ten Things I Wish Weren't Dead or Dying

The phrase "cumulative exhaustion" floated past this week, on the breakneck pace of change in the way we live now. Damn, that rang a bell. How to characterize the way life feels these days, online and “IRL”? It feels like my brain is swelling, while my skull is shrinking. It feels like they’re speeding up a treadmill, and things I love that can’t keep up are just flying off left and right. I used to be mildly horrified when older folks would say, “I’m glad I won’t be around to see it,” when “it” was some incomprehensible predicted change. You know, lunar vacation colonies or bionic bodies or food in a pill. Now I catch myself saying it.

The phrase "cumulative exhaustion" floated past this week, on the breakneck pace of change in the way we live now. Damn, that rang a bell. How to characterize the way life feels these days, online and “IRL”? It feels like my brain is swelling, while my skull is shrinking. It feels like they’re speeding up a treadmill, and things I love that can’t keep up are just flying off left and right. I used to be mildly horrified when older folks would say, “I’m glad I won’t be around to see it,” when “it” was some incomprehensible predicted change. You know, lunar vacation colonies or bionic bodies or food in a pill. Now I catch myself saying it.

The “future” used to be better, actually—the World’s Fair fantasies of housecleaning robots and flying cars. But as this Wonder Years kid approaches her AARP years, she notes a pattern: The World’s Fair stuff turns out to be largely bullshit, and the real surprises are rather hellish more often than not. We got Roombas and underwhelming electric cars. But hey, we also got cell phones and social media and Internet porn and cyberbullying and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. And climate change. Didn’t see those coming, did you?

The “future” used to be better, actually—the World’s Fair fantasies of housecleaning robots and flying cars. But as this Wonder Years kid approaches her AARP years, she notes a pattern: The World’s Fair stuff turns out to be largely bullshit, and the real surprises are rather hellish more often than not. We got Roombas and underwhelming electric cars. But hey, we also got cell phones and social media and Internet porn and cyberbullying and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. And climate change. Didn’t see those coming, did you?

And with the Rise of the Machines comes the fall of...so much else. Although the poor millenials get blamed for “killing” things, from conversation to cursive writing, my fellow “Boomers” are responsible for their share of casualties. Some of these things may deserve to die. (I’m looking forward to an old age in which bingo and golf are extinct.) But no single demographic seems to have administered the coup de grâce to the familiar, the simple, the good. It’s as if post-modernism met the Internet and released a mutating virus with diverse hosts.

Just for the hell of it, being an old magazine editor (see #1), I've come up with a Top 10 List, off the top of my head, of things that matter terribly to me and have languished on my (quite recent) watch. What’s in your Top 10?

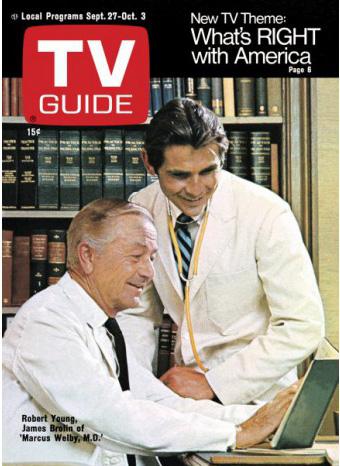

James Jarche, Science & Society1. Magazines. I always loved them, dreamed of writing and editing them, and studied journalism to make my dream come a little bit true, working for travel and health "books" and, once, getting a cover story for The American Spectator. (See #10, below.) Many magazines, of course, hang on, and digital "content" abounds. But opening a magazine freshly arrived through the mail slot is a joy that’s so last century.

James Jarche, Science & Society1. Magazines. I always loved them, dreamed of writing and editing them, and studied journalism to make my dream come a little bit true, working for travel and health "books" and, once, getting a cover story for The American Spectator. (See #10, below.) Many magazines, of course, hang on, and digital "content" abounds. But opening a magazine freshly arrived through the mail slot is a joy that’s so last century.

2. Newspapers, the New York Times in particular. The Gray Lady was the air I breathed as a New Yorker. I reluctantly gave up the dead-tree Times when their erratic delivery service seemed to acknowledge its irrelevance, and I ditched the online edition when it morphed into a weird, elitist liberal echo chamber with near-zero Metro coverage. Now, with the tabloids reduced to tatters, there virtually is no Metro coverage. Some real journalism hangs on, under economic and political siege, but only just.

2. Newspapers, the New York Times in particular. The Gray Lady was the air I breathed as a New Yorker. I reluctantly gave up the dead-tree Times when their erratic delivery service seemed to acknowledge its irrelevance, and I ditched the online edition when it morphed into a weird, elitist liberal echo chamber with near-zero Metro coverage. Now, with the tabloids reduced to tatters, there virtually is no Metro coverage. Some real journalism hangs on, under economic and political siege, but only just.

Ally Brosh, "Hyperbole and a Half"3. Blogs. If you’re reading this, I’ll bet you don’t have much company. There was a brief interlude, after the Internet but before social media, when it seemed as if citizen journalists, with a gloriously low bar to entry, would repopulate the media landscape, forming engaged communities and letting a thousand flowers bloom. Bloggers still blog, but any post bigger than a caption risks being “TLDR.” The firehose of social media, instead of watering blogs, has drowned them, with a numbing stream of pictures, GIFs, and memes. “Long form” posts now carry sheepish warnings: “Two-minute read.”

Ally Brosh, "Hyperbole and a Half"3. Blogs. If you’re reading this, I’ll bet you don’t have much company. There was a brief interlude, after the Internet but before social media, when it seemed as if citizen journalists, with a gloriously low bar to entry, would repopulate the media landscape, forming engaged communities and letting a thousand flowers bloom. Bloggers still blog, but any post bigger than a caption risks being “TLDR.” The firehose of social media, instead of watering blogs, has drowned them, with a numbing stream of pictures, GIFs, and memes. “Long form” posts now carry sheepish warnings: “Two-minute read.”

4. My beloved Catholic Church. Two waves of horror: the predator priests, and the preening demons in the hierarchy who covered them up or outdid them in corruption. It is my theology that the Church cannot die, but (at least in the West) it is withering and will rebloom, probably after my lifetime, looking very different. For this Caucasian mutt of dilute Irish-German extraction, the demise of the mid-century model of American Catholicism is quite literally the death of my culture.

4. My beloved Catholic Church. Two waves of horror: the predator priests, and the preening demons in the hierarchy who covered them up or outdid them in corruption. It is my theology that the Church cannot die, but (at least in the West) it is withering and will rebloom, probably after my lifetime, looking very different. For this Caucasian mutt of dilute Irish-German extraction, the demise of the mid-century model of American Catholicism is quite literally the death of my culture.

5. Catholic education, its decline not wholly related to #4 above. Catholic "teaching" makes headlines when it zaps a third rail in the culture wars, but no one has "taught" it for decades. And now, after the long dark age of catechesis, they are literally turning out the lights in Catholic schools. Or at least they're doing so in the great cities where they served and formed generations of poor and working-class youth, for a host of despicably shoddy excuses. Colleges are doing alright, but only by burying their Catholic identity in the Zeitgeist. Where is the next generation of Catholics being formed? Oh, they're not. Among millenials, baptisms and weddings have slipped away as essential touchpoints; now even funerals are being made over into DIY secular "rituals." Jesus wept.

5. Catholic education, its decline not wholly related to #4 above. Catholic "teaching" makes headlines when it zaps a third rail in the culture wars, but no one has "taught" it for decades. And now, after the long dark age of catechesis, they are literally turning out the lights in Catholic schools. Or at least they're doing so in the great cities where they served and formed generations of poor and working-class youth, for a host of despicably shoddy excuses. Colleges are doing alright, but only by burying their Catholic identity in the Zeitgeist. Where is the next generation of Catholics being formed? Oh, they're not. Among millenials, baptisms and weddings have slipped away as essential touchpoints; now even funerals are being made over into DIY secular "rituals." Jesus wept.

6. Television. Ah, TV: as simple as flipping a dial, a cultural force as unifying and ubiquitous as the air through which it traveled. Now it's just one more complicated private domain. We finally got a “smart” TV and now we struggle and argue and pay extra for this and that. Some of it is marvelous, but much of the best we can’t afford. I signed up for one cool-sounding “channel” only to find we couldn’t watch it on the only “platform” we use—an actual television set. The boob tube got smarter, we didn’t.

6. Television. Ah, TV: as simple as flipping a dial, a cultural force as unifying and ubiquitous as the air through which it traveled. Now it's just one more complicated private domain. We finally got a “smart” TV and now we struggle and argue and pay extra for this and that. Some of it is marvelous, but much of the best we can’t afford. I signed up for one cool-sounding “channel” only to find we couldn’t watch it on the only “platform” we use—an actual television set. The boob tube got smarter, we didn’t.

7. Food. I call it the “guilt list”: Is tuna killing the dolphins? Is red meat killing us? Are cage-free chickens really happier? Are carbs really the problem, or is it fat? I can’t afford organic, so that decision’s off the table, but everything else is a supermarket-aisle moral struggle. I worked the “healthy food” beat as an editor and writer for years, and even I can’t keep up. And of course, there’s the biggest struggle of all: being able to afford anything but pasta and the Dollar Menu.

7. Food. I call it the “guilt list”: Is tuna killing the dolphins? Is red meat killing us? Are cage-free chickens really happier? Are carbs really the problem, or is it fat? I can’t afford organic, so that decision’s off the table, but everything else is a supermarket-aisle moral struggle. I worked the “healthy food” beat as an editor and writer for years, and even I can’t keep up. And of course, there’s the biggest struggle of all: being able to afford anything but pasta and the Dollar Menu.

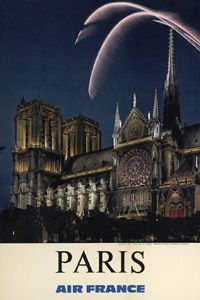

8. Travel. Even if some day I could “see the world,” it’s not the world I dreamed of seeing. “Globalized” destinations, including my own city, are blurring together, and not just thanks to McDonalds and Starbucks. Whether from entitled mobs of affluent tourists from rising economies or tragic encampments of migrant refugees from gutted ones (or both—see: Paris), so many legendary sites are culturally altered and reeling under the strain. (Selfish perspective, I know, but a moot point, since I can’t afford to go and fight the crowds anyway.) Heck, even Notre Dame didn't wait for me.

8. Travel. Even if some day I could “see the world,” it’s not the world I dreamed of seeing. “Globalized” destinations, including my own city, are blurring together, and not just thanks to McDonalds and Starbucks. Whether from entitled mobs of affluent tourists from rising economies or tragic encampments of migrant refugees from gutted ones (or both—see: Paris), so many legendary sites are culturally altered and reeling under the strain. (Selfish perspective, I know, but a moot point, since I can’t afford to go and fight the crowds anyway.) Heck, even Notre Dame didn't wait for me.

9. Health care. My pediatrician made house calls with a shiny black bag. Back then, when we were boldly heading to the moon, it wasn't routine to go bankrupt from cancer (you just died from it). Now we have "health care networks," and insurers who decide what they can do for us. Ours offers “telemedicine,” wherein I can set up a webcam and, presumably, cough at my screen to a stranger. Most people I know, even those with insurance, live in terror of major illness or injury as the harbinger of economic catastrophe, and “GoFundMe” is the new normal for cancer care. How did we get here? (Oh, and still no cure for lots of cancers.)

9. Health care. My pediatrician made house calls with a shiny black bag. Back then, when we were boldly heading to the moon, it wasn't routine to go bankrupt from cancer (you just died from it). Now we have "health care networks," and insurers who decide what they can do for us. Ours offers “telemedicine,” wherein I can set up a webcam and, presumably, cough at my screen to a stranger. Most people I know, even those with insurance, live in terror of major illness or injury as the harbinger of economic catastrophe, and “GoFundMe” is the new normal for cancer care. How did we get here? (Oh, and still no cure for lots of cancers.)

10. Conservatism. Ah, the Right, dashing hearthrob of my youth. "We had brains then," to paraphrase Nora Desmond. I worked for National Review in college, revered Bill Buckley and James Burnham, was drawn to the intellectual rigor, feisty good humor and moral robustness of the Right—both the badass libertarians and the erudite cultural traditionalists. The so-called “Right” today? Need I say more? The bragging, ignorant pustule in the White House and his minions, fueled by the screeching blond harpies on Fox News, are killing conservatism and sowing the ground with salt for at least a generation. As I say to my agonizing liberal friends, if you think it’s hard to be a “progressive” these days, try holding your head up as a conservative.

10. Conservatism. Ah, the Right, dashing hearthrob of my youth. "We had brains then," to paraphrase Nora Desmond. I worked for National Review in college, revered Bill Buckley and James Burnham, was drawn to the intellectual rigor, feisty good humor and moral robustness of the Right—both the badass libertarians and the erudite cultural traditionalists. The so-called “Right” today? Need I say more? The bragging, ignorant pustule in the White House and his minions, fueled by the screeching blond harpies on Fox News, are killing conservatism and sowing the ground with salt for at least a generation. As I say to my agonizing liberal friends, if you think it’s hard to be a “progressive” these days, try holding your head up as a conservative.

So there you go, ten dust-biters without even trying too hard. I didn’t even get to global warming, the transformation of Brooklyn to Dubai, or the shitty hollowed-out job market that is sucking our kids’ souls. Or late-term abortion, the last fragile stumbling block to the deadened conscience of the West, now trampled under the onslaught of the culture of death.

And do not get me started on “gender.” Or Tinder. Or Fiverr.

And do not get me started on “gender.” Or Tinder. Or Fiverr.

Urrr.

Before the parade passes by

That's the Crazy Stable—at right, behind a Cambodian temple procession that passed by yesterday on a beautiful spring afternoon.

The folks from Watt Samakki on the next block had a festival going on, and I was unloading groceries as they came up the block, chanting, beating drums, and ringing bells. A masked reveler blew me kisses.

The fabulous little parade jolted me with nostalgia for the surreal kaleidoscope of cultures that glimmered around us 32 years ago. We moved to "Caribbean Flatbush," but actually, to a borderland where almost anything seemed possible. Our first next-door neighbors were from Trinidad on the left, Haiti on the right; the unofficial block "mayor" was a feisty Jewish bagel-baker who scoffed at white flight, as had at least a half-dozen other aging white homeowners.

The fabulous little parade jolted me with nostalgia for the surreal kaleidoscope of cultures that glimmered around us 32 years ago. We moved to "Caribbean Flatbush," but actually, to a borderland where almost anything seemed possible. Our first next-door neighbors were from Trinidad on the left, Haiti on the right; the unofficial block "mayor" was a feisty Jewish bagel-baker who scoffed at white flight, as had at least a half-dozen other aging white homeowners.

Back then, emissaries from all over the globe would sweep by unpredictably. I once looked out the window to see a man dressed from head to foot in a shaman-like costume made of straw, dancing fiercely all alone and chanting in Kréyol. For several summers, a wild and glorious ra-ra band roamed the edges of Prospect Park on Sunday nights, making sonorous chaos. Also in summer would come a truck from Alabama, full of watermelons. It would stop on the corner and shy black men with deep Southern accents would emerge, selling the lot in an hour as word spread and neighbors hurried over on foot.

And that was only the block! Over in the Parade Grounds, the football (I mean football) players converged for their "beautiful game" daily, from Africa, South America, South Asia, playing their music afterwards on the sidelines to accompany epic picnics. Down on Church Avenue, Haitian ladies laid out herbs and spices on the sidewalk where everyone, even Russians from Brighton Beach, came to scour the bargain stores. Once, I waited at the check-out behind a Cambodian man who pushed forward a few dollar boxes of ramen with hands that appeared to have been crippled from torture.

And that was only the block! Over in the Parade Grounds, the football (I mean football) players converged for their "beautiful game" daily, from Africa, South America, South Asia, playing their music afterwards on the sidelines to accompany epic picnics. Down on Church Avenue, Haitian ladies laid out herbs and spices on the sidewalk where everyone, even Russians from Brighton Beach, came to scour the bargain stores. Once, I waited at the check-out behind a Cambodian man who pushed forward a few dollar boxes of ramen with hands that appeared to have been crippled from torture.

From killing fields to playing fields, came our neighbor monks. So many others came, too, most recently a wave of house-proud Bangladeshi contractors. But every year, there are more white faces among the newcomers. Blessed with affluence, they tend to fix up a rambling wooden house impeccably in record time; so far, none of these old piles has fallen to the wrecking ball, unlike fast-changing precincts to the east of us convulsed by tear-downs. But this real-estate feeding frenzy has turned it all into a tense zero-sum game: Gentrification. Displacement. Air rights. Air BnB. "Privilege." "Pioneering." A whole vocabulary for being adversaries instead of neighbors; decades-old conversations with a sharp new edge. Our poor house, in the condition we found it, would now mark it for the wrecking ball. Brooklyn no longer has much room for those of modest means, unless you got in years ago and hung on. It offers no mercy to teachers, or artists, or home health aides, or our children, of any color, in its high-rise future. (Unless they are "in finance," apparently. Those "in finance" must be the ones who now populate the air by right.)

Luxury was not a word you would have associated with our block back in the day. Raw possibility, yes, and most of all, people, amazing people. Immigrants, mostly (those monstrous threats, we are warned) who brought us hot meals, carried trash to our dumpster, and assured us, "It's a good house, but it takes time." Their celebrations bubbled up in our lives like an underground stream, not curated by some museum but just happening on the street. We weren't invited, we weren't excluded. We waved. They waved back.

Luxury was not a word you would have associated with our block back in the day. Raw possibility, yes, and most of all, people, amazing people. Immigrants, mostly (those monstrous threats, we are warned) who brought us hot meals, carried trash to our dumpster, and assured us, "It's a good house, but it takes time." Their celebrations bubbled up in our lives like an underground stream, not curated by some museum but just happening on the street. We weren't invited, we weren't excluded. We waved. They waved back.

It seems like only yesterday.

Dignity in diapers

Alfie Evans/Daily Mirror

Alfie Evans/Daily Mirror

Ah, "death with dignity."

For a long time, that was the "compassionate" crack in my armor in defense of life: end-of-life care, because I have seen it done so badly, over and over. Once, visiting my mother in hospital, I watched in horror as the staff roughly inserted an enteral feeding tube into an ancient, unconscious lady in the next bed; she lay curled in a fetal position, repeating, "Mama." I found myself nodding that we needed "death with dignity," since human dignity is my deepest value.

But some writer—I wish I could remember who—pointed out that human dignity is based on: being human. Not being alert, peaceful, or without pain, or able to toilet oneself, or being cognizant of one's surroundings. Just being...human.

Vanessa Redgrave, "Evening" (2007)Our dignity does not lay upon us like a garment, with our worth stripped away by externalities. I want to die like a luminous Vanessa Redgrave character, fading gracefully and quickly. With dignity. Without tubes. But my dignity is impressed upon me by my Creator; if I do wind up helpless and burdensome, or even in agony, He has given us His own Son as a template that I can never (in the words of Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman) "be thrown away." His Son's earthly body, my church, stipulates that no one need degrade my dignity with "extraordinary means" to keep me alive—but neither may they dictate that my "dignity" be preserved by hustling me (or even helping me push myself) over the edge of death.

Vanessa Redgrave, "Evening" (2007)Our dignity does not lay upon us like a garment, with our worth stripped away by externalities. I want to die like a luminous Vanessa Redgrave character, fading gracefully and quickly. With dignity. Without tubes. But my dignity is impressed upon me by my Creator; if I do wind up helpless and burdensome, or even in agony, He has given us His own Son as a template that I can never (in the words of Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman) "be thrown away." His Son's earthly body, my church, stipulates that no one need degrade my dignity with "extraordinary means" to keep me alive—but neither may they dictate that my "dignity" be preserved by hustling me (or even helping me push myself) over the edge of death.

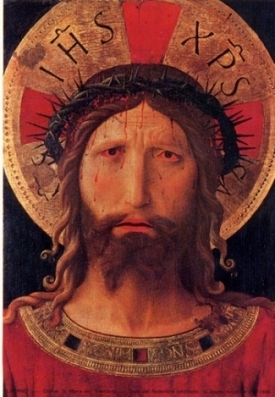

Fra Angelico, "Christ Crowned with Thorns"To care for those stripped of the world's signifiers of "dignity," whether intellectual capacity, sanity, continence, teeth, hygiene, material possessions, freedom, clothing, any of it, is to see (on His explicit instructions) the face of my Redeemer. To lose my world-approved dignity in any of those domains is to become one with Him in suffering. I saw this mutually conferred dignity many times at Calvary Hospice, where the staff tenderly fed and bathed and turned patients with cancer in their final weeks, sparing them brutal "interventions" but never, ever deliberately hastening death. Each, caregiver and patient, being Christ to the other.

Fra Angelico, "Christ Crowned with Thorns"To care for those stripped of the world's signifiers of "dignity," whether intellectual capacity, sanity, continence, teeth, hygiene, material possessions, freedom, clothing, any of it, is to see (on His explicit instructions) the face of my Redeemer. To lose my world-approved dignity in any of those domains is to become one with Him in suffering. I saw this mutually conferred dignity many times at Calvary Hospice, where the staff tenderly fed and bathed and turned patients with cancer in their final weeks, sparing them brutal "interventions" but never, ever deliberately hastening death. Each, caregiver and patient, being Christ to the other.

How easy it is to rhapsodize over our sublime human dignity while gazing at a Rembrandt, or watching Misty Copeland dance, or hearing Martin Luther King orate. How easy to treasure life when you hold a thriving baby or sit at the knee of a spry, healthy grandparent. It's even easy to marvel at the dignity of the frail, if they're heroic enough, a Mother Teresa here and a Stephen Hawking there. But how difficult it is, when life fades, or arrives broken, or leaks uncontrollably from various orifices.

Francesco Bassano, "Parable of the Good Samaritan" (detail)Bodily fluids, in fact, seem to be one of the breaking points in the world's definition of human dignity. For many of us, it's the ultimate taboo of vulnerability. For that reason, perhaps, this loss of control has become for me a stubborn sign that the crucified Christ is present, his side pouring forth its "water." I have my own private heroes' gallery of human dignity:

Francesco Bassano, "Parable of the Good Samaritan" (detail)Bodily fluids, in fact, seem to be one of the breaking points in the world's definition of human dignity. For many of us, it's the ultimate taboo of vulnerability. For that reason, perhaps, this loss of control has become for me a stubborn sign that the crucified Christ is present, his side pouring forth its "water." I have my own private heroes' gallery of human dignity:

- the gregarious owner of a guest farm in Pennsylvania whose lower jaw was lost to cancer, who communicated in cheerful notes and wore gauze pads sewn by his wife to absorb his saliva.

- The beloved art teacher at my daughter's high school who survived bladder cancer and made hilariously candid references to his "pee bag." (What an example to a classful of girls at the age when a blackhead seems like a catastrophe!)

- My cousin Rik, who returned to teaching periodonty after a spinal-cord injury deprived him of control of the lower half of his body at mid-life.

And I experienced it most vividly in caring for my Uncle Don in his very old age. (That's him, with a strawberry milkshake.) His care at the very end of life was exhausting and yes, to the "system" it was damned expensive. Yet he was radiant with joy, and delighted in receiving my ministrations. He did not need to be Vanessa Redgrave, fading elegantly. He was luminous in his own way. Can we see the light in others, that light of life that is the deepest dignity, from conception to something like natural death? Or can we only get an itchy trigger finger to put that light out forever, "for their own good"?